Fun Fact

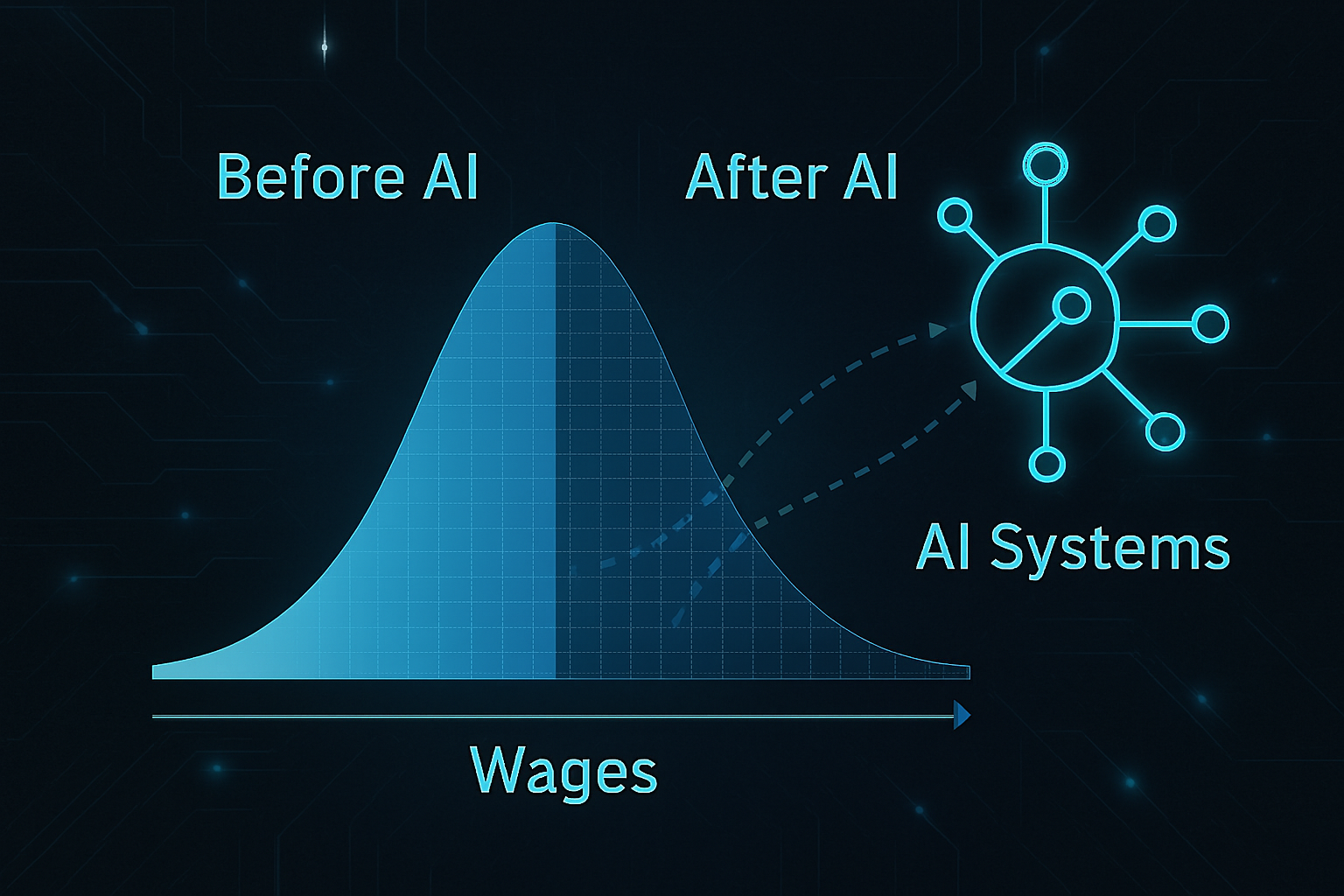

For decades, economic models predicted that automation would depress wages. New data suggests AI may be reversing that pattern.

AI Adoption Is Reshaping Wage Dynamics More Than Expected

A new working paper from Stanford University and the Barcelona School of Economics reports that artificial intelligence is raising average wages by 21 percent and reducing wage inequality across several sectors. The findings challenge long‑standing assumptions about how automation affects labor markets. For years, the dominant narrative was that technology would replace workers, depress wages, and widen inequality. The new data suggests a more complex and in some cases more optimistic picture.

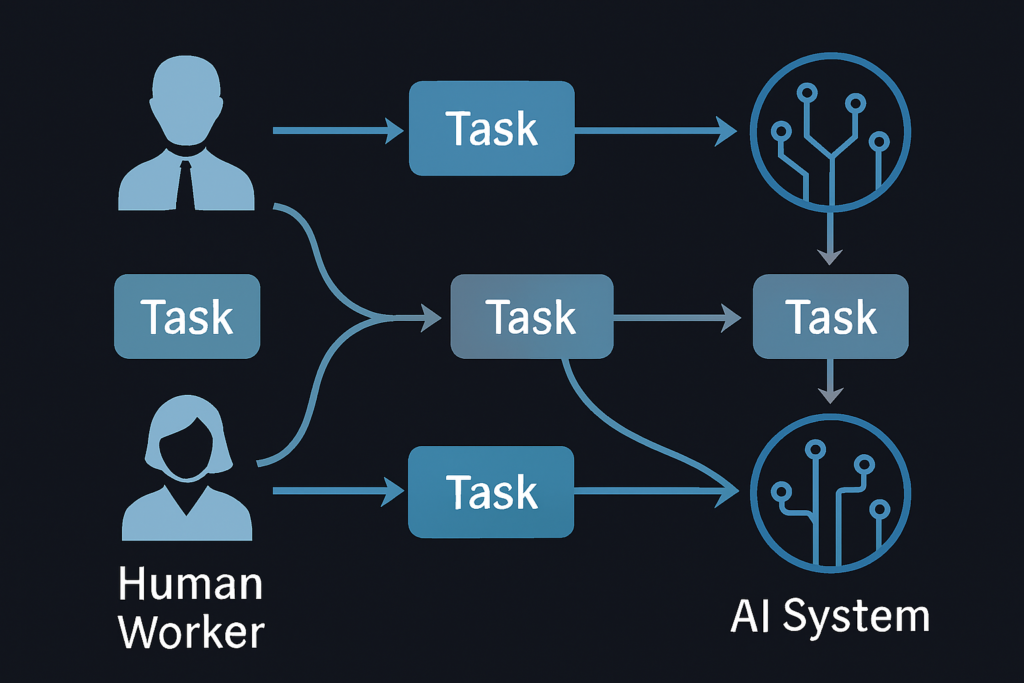

The study argues that AI is not simply automating tasks but reshaping the composition of work. Workers shift toward tasks where they have comparative advantage, while AI absorbs tasks that were previously bottlenecks. The result is a reallocation of labor rather than a displacement. This is not universal, and the effects vary by occupation, but the overall trend is notable.

The paper introduces a dynamic task‑based model to explain how workers adapt when AI changes the productivity of specific tasks. Instead of treating occupations as fixed bundles of responsibilities, the model assumes that tasks can be reorganized. Workers move toward tasks where human judgment, context, or coordination still matter. AI handles tasks that benefit from scale, consistency, or pattern recognition.

This framework helps explain why wages rise. When workers shift toward higher‑value tasks and AI increases overall productivity, the gains can be shared. The study finds that wage compression occurs because lower‑skilled workers benefit disproportionately from the reallocation. They move into tasks that were previously inaccessible or undervalued, while AI handles the more routine components.

A Different Pattern From Previous Automation Waves

Historically, automation has had uneven effects. Industrial automation displaced manual labor. Software automation displaced clerical work. In both cases, the gains were concentrated among higher‑skilled workers. The new findings suggest that AI may follow a different pattern.

One reason is that AI is not tied to a specific industry. It is a general‑purpose technology that affects a wide range of tasks across sectors. Another reason is that AI can complement lower‑skilled workers by giving them access to tools that previously required specialized training. For example, customer support agents using AI‑powered assistants can handle more complex queries. Warehouse workers using AI‑driven optimization tools can manage workflows that once required technical expertise.

The study also notes that AI adoption tends to increase productivity at the firm level. When firms become more productive, they often expand. Expansion increases demand for labor, which can offset displacement effects. This is not guaranteed, but it is a pattern observed in several industries adopting AI tools.

How Task Reallocation Works in Practice

The task‑based model used in the study provides a useful lens for understanding how AI affects work. Instead of assuming that AI replaces entire jobs, the model breaks jobs into tasks. Some tasks are automated, some are augmented, and some remain unchanged. Workers shift toward tasks that require human capabilities.

This reallocation can raise wages in several ways. First, workers spend more time on tasks that are harder to automate and therefore more valuable. Second, AI increases the productivity of the overall workflow, which can increase the marginal product of labor. Third, firms that adopt AI may become more competitive, leading to expansion and higher labor demand.

The study provides examples across multiple sectors. In finance, analysts use AI to process large datasets, allowing them to focus on interpretation and strategy. In healthcare, AI handles administrative tasks, freeing clinicians to spend more time with patients. In logistics, AI optimizes routing and scheduling, while workers handle exceptions and coordination.

Distributional Effects and Wage Compression

One of the most notable findings is the reduction in wage inequality. The study reports that lower‑skilled workers experience larger wage gains than higher‑skilled workers. This is unusual. Previous automation waves tended to widen inequality by disproportionately benefiting workers with higher education or specialized skills.

The explanation lies in task reallocation. Lower‑skilled workers move into tasks that were previously out of reach because AI handles the technical or routine components. This raises their productivity and therefore their wages. Higher‑skilled workers also benefit, but the gains are smaller in percentage terms.

The result is wage compression. The distribution narrows. This does not eliminate inequality, but it reduces the gap. The study emphasizes that this effect depends on the nature of the tasks and the degree of AI adoption. It is not universal, but it is significant in the sectors studied.

Limitations and Open Questions

The study acknowledges several limitations. The data comes from specific sectors and may not generalize to the entire economy. The long‑term effects are uncertain. AI adoption may accelerate, slow down, or shift in unexpected ways. The model assumes that workers can reallocate tasks, but this may depend on training, mobility, and institutional factors.

There are also questions about the sustainability of wage gains. If AI continues to improve, tasks that are currently human‑dominated may eventually be automated. The study does not predict this, but it notes the possibility. The effects may also vary by country, depending on labor markets, regulations, and education systems.

A Gradual but Meaningful Shift

Despite the uncertainties, the findings suggest that AI is reshaping labor markets in ways that differ from previous automation waves. The shift is gradual, not sudden. It is structural, not cyclical. And it is driven by task reallocation rather than job elimination.

The broader implication is that AI may not simply replace workers but reorganize work. This reorganization can raise wages, reduce inequality, and increase productivity. It is not guaranteed, and it depends on how firms adopt AI and how workers adapt. But it is a meaningful shift.

Conclusion

The emerging evidence suggests that AI is altering the relationship between automation and wages. Instead of depressing wages and widening inequality, AI appears to be raising wages and narrowing gaps in the sectors studied. The mechanism is task reallocation rather than displacement. Workers move toward tasks where human capabilities matter, while AI handles routine or scalable tasks.

This does not resolve all concerns about automation, nor does it guarantee similar outcomes across all industries. But it indicates that AI may follow a different pattern from previous technologies. The direction of travel is becoming clearer: AI is not simply replacing labor but reshaping it, and the economic effects are more nuanced than expected.