Fun Fact: The Immense Scale of Compute

In 2023, training GPT-4 required thousands of high-end GPUs. By 2026, simply running AI assistants for millions of users will require millions of physical units spread across continents. The bottleneck didn’t disappear — it multiplied. While the software world celebrates new benchmarks, the physical world is quietly struggling to provide the silicon, energy, and cooling needed to sustain them.

For the past two years, the AI conversation has revolved almost entirely around models.

Bigger models.

Smarter architectures.

More parameters.

More demos.

More impressive charts.

That narrative still dominates headlines, conference stages, and investor decks. It’s familiar, comfortable, and easy to sell. But beneath it, something quieter — and far more limiting — has been taking shape.

The next phase of AI will not be decided by who trains the smartest model.

It will be decided by who can actually run AI at scale, day after day, without stressing the systems that make it possible.

That question has very little to do with prompts or interfaces. It lives deeper, inside hardware limits, infrastructure tradeoffs, and energy constraints that no amount of clever software can simply wish away.

The Illusion of Endless Model Progress

On paper, AI progress still looks exponential. New architectures appear frequently. Benchmarks climb. Costs per token fall. Each release promises efficiency gains that seem to cancel out the limitations of the previous generation.

In practice, progress has started to feel heavier — almost slower, despite the headlines.

Training a new model is no longer the hardest part. The real challenge begins after the model works, when it has to be deployed, stabilized, monitored, and kept alive under real-world load.

At scale, infrastructure complexity now rivals the neural network itself. Sometimes it even overshadows it.

Large AI systems depend on physical realities that software abstractions cannot hide forever:

- Dense GPU clusters packed into limited space

- Memory bandwidth struggling to keep pace with compute

- Cooling systems operating close to thermal limits

- High-throughput networking under constant stress

- Reliable energy supply negotiated years in advance

- Physical land, permits, and zoning approvals

These are not software problems waiting for optimization.

They are physics problems — and physics does not scale at the speed of hype, no matter how confident the roadmap sounds.

When Compute Isn’t the Problem, Memory Is

One of the least discussed constraints in modern AI is not raw compute power, but memory movement.

This is where the so-called “Memory Wall” quietly shapes the future of performance.

Processing units have grown dramatically more powerful. Memory bandwidth has not kept pace. As models grow larger, the cost of moving data between memory and processor becomes a bottleneck that raw FLOPs cannot overcome.

A chip can be extraordinarily fast and still spend most of its time waiting.

This is why high-bandwidth memory has become one of the most contested components in the semiconductor supply chain. It’s also why future gains may come less from clever algorithms and more from physical design choices: stacking memory vertically, shortening data paths, and reducing latency by margins that used to feel irrelevant.

At scale, those margins suddenly matter.

The future of AI performance may depend less on how smart a model is — and more on how efficiently a chip can feed itself.

GPUs Were Inevitable — But They’re No Longer Enough

GPUs earned their central role in the AI boom. Their parallel architecture fit early deep-learning workloads almost perfectly, and their flexibility made them the obvious choice for experimentation.

That dominance, however, came with tradeoffs.

As AI moved from research to production, companies ran into an uncomfortable reality: relying exclusively on general-purpose GPUs at scale is expensive, inefficient, and strategically limiting.

This has triggered a quiet but decisive shift toward application-specific chips.

Not because it sounds futuristic.

Because the math leaves little choice.

If you don’t control the silicon, you don’t fully control your costs, your margins, or your roadmap. Over time, that lack of control compounds.

The next cycle won’t be about who buys the most GPUs.

It will be about who designs hardware that fits their workloads — and discards everything else.

If you’re looking at how major networks are positioning themselves in 2026, this deep dive comparing The AI Energy Crisis: Why 2026 Is the Year of the “Electric Wall” provides useful context for why the next wave of AI will be constrained less by benchmarks and more by physical infrastructure:

https://techfusiondaily.com/ai-energy-crisis-electric-wall-2026/

The Fragility of the Silicon Supply Chain

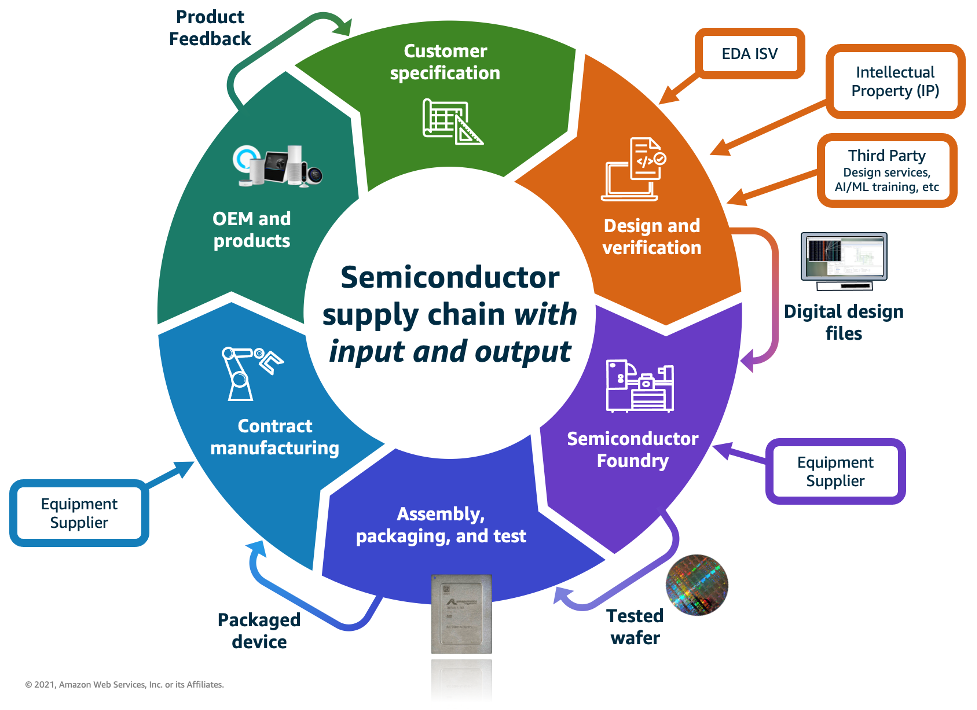

There is another reality that rarely makes it into optimistic AI narratives: the advanced chip supply chain is astonishingly concentrated.

A small number of companies control the most critical steps. If one advanced fabrication facility goes offline, timelines slip everywhere. If one link breaks, entire product strategies stall.

This fragility explains why governments are treating semiconductor manufacturing as a matter of national security rather than industrial policy. It also explains why “digital sovereignty” is no longer abstract — it’s operational.

AI ambition now depends on geopolitical stability in ways software teams rarely had to factor into planning before.

That alone should make the industry pause.

Energy: The Constraint That Refuses to Stay Invisible

Every large AI system eventually runs into the same question — usually later than it should:

Where does the electricity come from?

AI inference consumes far more energy than traditional computing. As AI products become always-on, real-time, and globally accessible, power demand stops being a rounding error and starts becoming a design constraint.

Some companies are exploring nuclear partnerships. Others are building data centers next to renewable clusters. In some regions, permits are denied unless sustainability plans are proven in advance.

This isn’t a distant concern.

AI is not just a compute problem.

It is an energy problem — and energy moves slowly, regardless of how fast software iterates.

Edge AI: Shifting Intelligence Closer to the User

One response to mounting cloud pressure is pushing computation closer to users.

Edge AI isn’t a buzzword; it’s a practical compromise.

Smartphones now ship with dedicated neural processing units. Laptops include on-device accelerators. Consumer hardware is quietly absorbing workloads that once required remote servers.

This reduces latency and improves privacy, but it introduces new constraints: efficiency, heat, and battery life. Suddenly, every watt matters.

The winner of the next cycle may not be the most powerful chip, but the one that delivers useful intelligence without turning devices into pocket heaters.

Heat Is Becoming the Real Enemy

As chips grow denser, heat becomes the limiting factor.

Traditional air cooling is nearing its practical limits. Data centers are moving toward liquid cooling, immersion systems, and complex thermal management strategies that would have sounded extreme just a decade ago.

At this point, designing an AI data center looks less like software engineering and more like industrial thermodynamics.

You can scale compute.

You cannot negotiate with heat.

Scaling Has Physical Boundaries

Even if compute, memory, and energy all improve, AI still faces immutable physical limits.

Latency cannot beat the speed of light.

Heat must be dissipated.

Geography determines where data centers can exist.

These constraints don’t stop progress — but they shape it in ways roadmaps rarely acknowledge upfront.

They decide which ideas survive contact with reality.

AI Is Turning Into a Utility

At scale, AI begins to resemble a utility.

Every inference has a cost.

Every user adds load.

Every feature increases energy demand.

The companies that survive this transition will be the ones that think in terms of infrastructure economics, not just model performance.

AI is no longer just software.

It is a physical economy.

From AI Excitement to AI Reality

The industry is slowly leaving its spectacle phase.

The early question was simple:

What can AI do?

The current question is more uncomfortable:

What can we afford to run continuously, reliably, and at global scale?

That shift will slow launches. It will frustrate users. It will disappoint investors chasing infinite curves.

But it also signals maturity.

The future of AI will not be built on demos.

It will be built on infrastructure that holds when the excitement fades.

The Question That Actually Matters

Models will continue to improve. Benchmarks will rise. Interfaces will get smoother.

But the next tech cycle will not belong to whoever builds the smartest AI.

It will belong to whoever can keep it running.

So the real question is no longer about breakthroughs.

It’s about endurance.

Who will have the power — literally — to sustain the AI future everyone is racing toward?

Sources

TechFusionDaily

Original editorial analysis

Originally published at https://techfusiondaily.com

One thought on “Why AI Hardware — Not Models — Will Decide the Next Tech Cycle”